Nearly all early stage business plans have some form of exponential or hockey stick shaped growth plan. Whether an early stage company or an established enterprise, how does an investor or company executive know whether that growth plan is outrageous hyperbole or representative of the opportunity and worthy of increased investment? There are two important elements to any revenue plan: 1) How big is the market, and 2) How attractive is the value proposition driving the revenue plan. Assessing market size is largely an exercise in intelligent data collection and analysis. Understanding and quantifying the value proposition for a given product or service is significantly more challenging and can be largely subjective if not done correctly.

In the absence of meaningful data to support the market opportunity and/or the value proposition, the process for smoothing out these often unrealistic expectations or “closing the gap” are varied. When the plan is for a new product introduction in larger organizations, there is generally a more data-driven process by which these plans get refined and the revenue model is validated to the extent possible. When the growth plan is part of an early stage business that is seeking investment, many investors draw on experience to discount these “unrealistic” plans in their analysis of the business without significant thought as to the assumptions used by the entrepreneur(s) who created the plan, other than attributing them to irrational exuberance.

An investor or business leader can easily identify risk that needs additional explanation when looking at a pro-forma P&L. At the core of many of these plans is the belief there will be substantial leverage on Selling, General & Administrative Expenses (SG&A) at some point in the future as compared to the product launch phase. While it is true that sales effectiveness and efficiency will increase over time, the rate at which this grows is often overstated. Correcting this can take two forms: either reduce the top-line growth expectations based on a more realistic return on SG&A, or increase the SG&A to support the top-line growth opportunity. In the large organization model where there is sufficient performance history for comparison, the assumption is that leverage will return to the norm for the business after the product is fully launched and in the commercial channel(s), and SG&A is adjusted accordingly. In the early stage business where there is no performance history, the tendency for investors is not to adjust SG&A but rather to dramatically reduce the top-line revenue to recast the growth to more straight-line or at least a more gradual hockey stick shape.

To convince investors or senior leaders that a business plan is valid and the hockey stick represents real opportunity worthy of investment, the entrepreneur or product manager must demonstrate that the market opportunity is sufficiently characterized and validated and most importantly, the value proposition is what is driving the increased leverage on SG&A.

Analyze Your Market

The reality is that in any organization any increased leverage beyond the product introduction phase must be substantiated with an analysis of the market. This is particularly important for the early-stage businesses as the entrepreneur should not assume that investors will take on this responsibility. It is incumbent on the entrepreneur to help investors understand why his/her business is more capable of realizing exponential growth than the myriad other plans investors review.

The analysis of the market should start with establishing how large the market is for the primary product or service of the business. A key yet common mistake entrepreneurs make is to overstate the total available market by greatly exaggerating the opportunity by including revenues that are not accessible to the company. The size of the market should be characterized by the revenue directly associated with the sale of the product or service, not the overall size of the market for all products or services sold into that market. For example, the market size for a medical device used as an implant in knee replacement should be the combined revenues of all implants for knee replacements and exclusive of surgeon, hospital and other ancillary revenues associated with the procedure. From there, the market should be further refined to include only those revenues from comparable devices that target the indications of the specific device. In the example where a new device or innovation displaces other costs within a given workflow, it is not appropriate to simply expand the market size by including those displaced costs. Some fraction of the displaced costs should be considered, but understanding the value to the customer is critical to validating exactly what that incremental revenue opportunity is.

With a realistic understanding of the actual size of the overall addressable market, one can then begin to estimate the share of that market the emerging business can realistically expect to capture and the rate at which that share gain can be realized. While working to refine the market from the top down, a bottoms-up view of the costs associated with generating that revenue should proceed in parallel.

This is another key area where many business plans break down. The operating expenses associated with the planned revenue are not realistic, and the leverage of SG&A becomes excessive and in many cases unbelievable.

Review and Refine Your Value Proposition

Validating exponential growth should also include continual review and refinement of the value proposition for the product or service. Assuming the value proposition is meaningful, the growth expectations then become dependent on awareness. The entrepreneur needs to demonstrate that their go-to-market plan ensures a sufficient number of potential customers are exposed to the product and that the methodology and costs of acquiring those leads, converting them to opportunities and then closing the sale is appropriately captured in the plan. While conversion or capture rates typically go down over time, entrepreneurs expect the early success to continue unabated and as a result, overstate the growth rate for the business and understate the costs associated with realizing that growth.

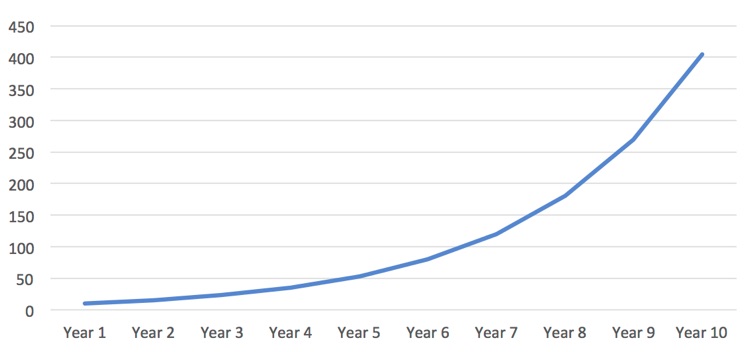

Consider the following hypothetical model where a new business proposes to experience 50 percent compounded growth in customers over a 10-year period. The 400 customers in year 10 may represent modest market penetration and look very reasonable to an entrepreneur. If you assume the available market is 4,000 customers, this would represent a 10 percent market share.

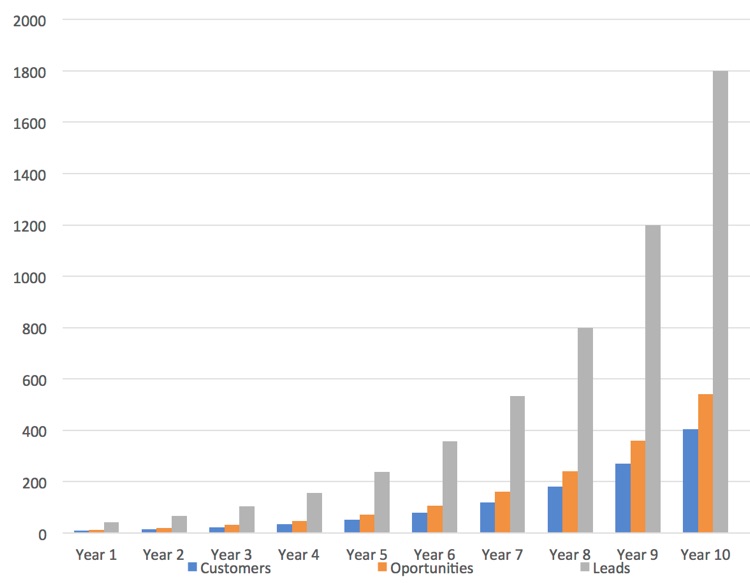

Looking a bit deeper into the model above and using a traditional go-to-market model where leads convert to opportunities which convert to sales, one can back into the funnel that is required to support the desired growth in customers. If one were to assume that a business had a particularly compelling value proposition where 30 percent of those being exposed to the product (leads) convert to opportunities and 75 percent of those opportunities actually purchase the product, the following chart shows the number of leads a business would need to generate to experience 50 percent compounded growth in customers over time.

In this purely hypothetical example, the business would need to generate nearly 4.5 leads for every actual customer it expects to gain and assuming there was no market growth, 45 percent of the market would have been exposed to the product and would be characterized as a “lead” by year 10.

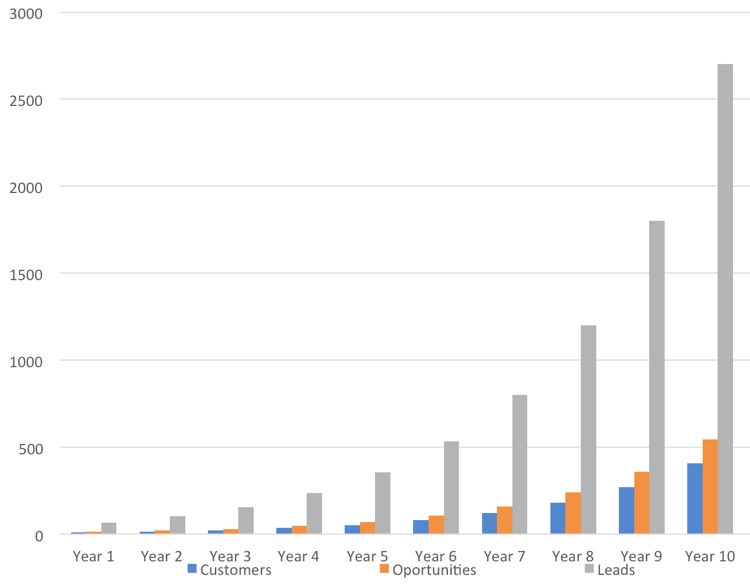

If we make a minor change to the assumption that 30 percent of leads convert to opportunities with only 20 percent converting, the chart now looks like the following:

Now, 67.5 percent of the total market has been exposed to the product (as a lead) and absent any significant market growth, the longer-term prospects for the business become less attractive.

While this is purely a math exercise at this juncture, the point is there are numerous factors that influence whether a hockey stick growth model is achievable. Those factors include:

- What is the market growth rate over the plan period?

- What is the rate that leads convert to opportunities? Is this constant over time?

- What is the rate that opportunities convert to sales? Is this constant over time?

- Is there an annuity that accompanies initial placements (service, consumables, etc.)?

While numerous factors influence the growth rate for a new product or business, the most important is the rate at which “leads” ultimately convert to customers.

While there are ways a business can influence this (e.g. sales force effectiveness), the more compelling the value proposition the greater the rate at which this occurs. In fact, the ratio of leads to customers is an excellent metric to track the value proposition for a product or business and will help investors determine how likely a new business venture is to realize the targeted growth.

This model also helps investors validate that the SG&A proposed will adequately support the projected growth rate as this is where unrealistic leverage appears in the outer years of a plan. As already mentioned, entrepreneurs can be overly optimistic when forecasting growth while not taking into consideration the underlying costs of maintaining the ratio of leads to customers.