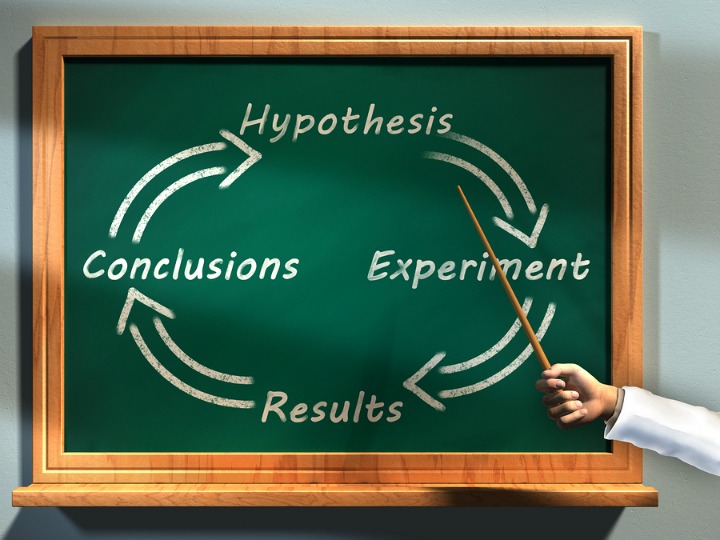

A sustainably innovative organization constantly learns and is comfortable with uncertainty. This type of organization seeks to remove uncertainty through experimentation that is designed to improve knowledge through two key actions: comparison of hypothesis with results and analysis of any differences between them.

Formulating a meaningful hypothesis on any unknown, from customer and market expectations to technical solutions for unsolved problems, requires some forethought about what is necessary to succeed with the given project. Optimizing and prioritizing the experiments necessary to gain the most valuable knowledge at a reasonable cost (in time and resources) also requires some forethought about what can go wrong and the consequences of incorrect assumptions or inability to achieve a certain result.

An innovative, learning organization extracts knowledge from every activity and sets up every activity to maximize the value of the knowledge it can extract.

This general concept of the importance of deliberate experimentation to innovate has been discussed in a multitude of innovation texts, including “Beyond the Idea” by Govindarajan and Trimble (which is a great text for larger organizations) and “Lean Startup” by Reis (which is a good text about what might be achievable in any organization).

The Tools for Process Improvement Originated from the Tools for Innovation

However, the idea of thoughtful experimentation, analysis and adaptation (i.e. pivoting) to improve on a process or product is much older and most clearly demonstrated in the practice of kaizen, which was adopted in Japan after World War II in order to improve on all aspects of business processes. A key element of kaizen is the company-wide adaptation of the scientific method to enable each employee to conduct experiments to improve his or her work.

The things that matter for effective learning and improvement haven’t changed much over the years, although the words we use to describe them and communicate to each other may vary from discipline to discipline. For example, much of the thought process for kaizen and Six Sigma was lifted from the scientific and engineering community and then primarily applied to continuous improvement of manufacturing and supply chain processes. Its application has since spread out to other business processes and is now finally making its way into the product development arena.

Physician, Heal Thyself!

This re-introduction has been a slow process as those of us who are scientists and/or engineers know—we don’t always take kindly to others claiming to know how we can best do our jobs, even if they are just telling us to go ahead and do what we were trained to do.

If you truly want your organization to be more innovative, immediately start understanding what you are doing, why you are doing it and what you expect to result from doing it before you actually do it.

This basic implementation of the scientific method is important for all new things you undertake, whether individually or as part of a larger team. As long as you take the initiative to think through these intentions and expectations, you will be able to learn from the result. Whether you succeed or fail, through examination of the result, you’ll have acquired the knowledge to gain competence as an organization. By this I mean you can apply this objective learning to institutionalize it by improving the process for the next pass.

My suggestion to the product development community is that we employ our experimental prowess not only to facilitate the next project but to evaluate and improve the process by which we do it. In this way we can start doing what we are best at to get better at what we are supposed to be doing.